Understand the Changes to NIST's Supply Chain Security Guidance

Note, this information included in this piece contains the most recent NIST updates as of 6/22/2022.

SP 800-161 Rev. 1 offers NIST’s latest guidelines on supply chain security, including new controls and metrics for cybersecurity supply chain risk management (C-SCRM), updated guidance on risk appetite and risk tolerance, and updates to accompany new authorities under the Federal Acquisition Supply Chain Security Act of 2018 (FASCSA) and to respond to the May 2021 Executive Order 14028.

This report explains the biggest changes within the update, details how the revisions affect most security teams and recommends ways to address them.

NIST SP 800-161 Rev. 1 Highlights

On May 5, 2022, NIST released NIST SP 800-161 Rev. 1 (Cybersecurity Supply Chain Risk Management Practices for Systems and Organizations), an update to its 2015 supply chain security guidance. This revision was already under way prior to the May 2021 release of Executive Order 14028 (Improving the Nation’s Cybersecurity), with the first call for comments released on Feb. 4, 2020. However, the revision was given additional standing and priority because it was listed as a task under the Executive Order. Highlights of the revision include new focus on:

- OT and IoT: This version adds “Cybersecurity” to the title because it is broader than the previous guidance, incorporating OT and IoT, in addition to information and communications technology.

- Supply chain interdependencies: The primary audience for the update is organizations that purchase, deploy, use and manage software from open source projects, third-party suppliers, developers, system integrators or external system service providers. The guidance is designed to help organizations integrate C-SCRM practices and requirements into their system acquisition and development lifecycle. It now recognizes the interdependency of multiple vendors and service providers within a system’s supply chain and incorporates considerations for vulnerabilities within vendor source code and configuration.

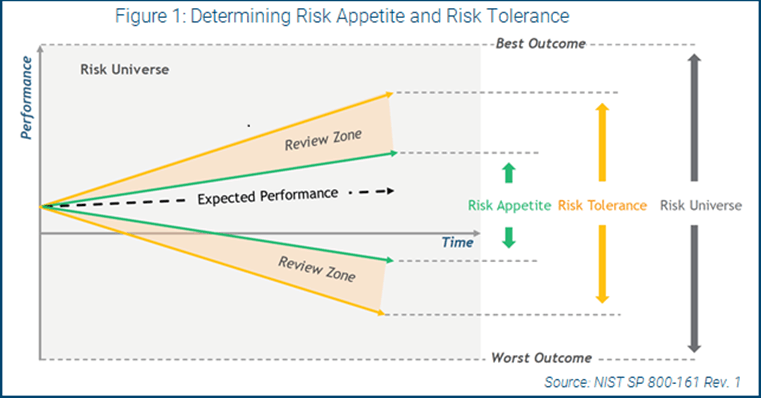

- Risk management: One significant, but overlooked, component of this update is the incorporation of enhanced risk management practices, specifically addressing organizational risk appetite and risk tolerance. With this new update, the executive leadership of the company now owns and is accountable for cybersecurity risks in the supply chain. Boards of directors and regulators now have heightened expectations for organizations to define a risk appetite and use risk tolerance levels to define their risk-taking and risk avoidance decisions.

READ: 4 Steps to Customize a Risk Framework

Figure 1 comes from NIST and provides a visual representation of how an organization defines a risk appetite, using upper bounds for risk-taking and lower bounds for risk avoidance. Optimal risk management is between these two boundaries and exceeding the risk appetite triggers a review by risk owners, including leadership, to determine if it is still within risk tolerance and to identify corrective actions.

The focus of this guidance is to provide an update on methods and practices to identify, assess and respond to cybersecurity risks throughout the supply chain—at all levels of an organization. The guidance is based on the latest NIST SP 800-53 Rev. 5 control update. A subset of 800-53 Rev. 5 controls relevant to C-SCRM are extracted and enhanced with additional guidance. In addition, new controls are added that are not included in the NIST control catalog (see Figure 2).

How This Update Affects Security Teams

NIST SP 800-161 Rev. 1 primarily affects federal government departments and agencies, contractors, and software vendors subject to the FASCSA of 2018 and Executive Order 14028. In addition, organizations that do not sell software products or services to the federal government or its contractors may find this guide useful to update their own supply chain security program.

Before jumping into the C-SCRM process, however, consider the size and scope of your firm. What is the breadth and depth of your vendor footprint, from cloud service providers to third-party software packages? How mature is your existing vendor risk management program, and how could it be updated to incorporate recommendations from this guidance?

NIST recommends tailoring this guidance using those factors, focusing first on identified foundational C-SCRM practices until you reach a base level of maturity. Then, you should move onto sustaining and enhancing practices. NIST also recommends organizations first conduct a risk assessment of their C-SCRM capabilities. Companies select security controls based on the NIST SP 800-53 Rev. 5 overlay (see Figure 2) and then tailor and implement those controls following the guidance in both documents. This includes consideration of your organization’s environment, operations, threats and data sensitivity.

For example, if you are just starting out in your C-SCRM program (foundational practices) and use an automated continuous integration/continuous delivery build process in your SDLC (a sustaining practice), you have some foundational work to complete before you can incorporate C-SCRM best practices into your existing delivery process.

READ: Top Strategies for Identifying Software Supply Chain Risks

Tips to Get Started

NIST SP 800-161 Rev. 1 includes several changes and updates designed to enhance your supply chain visibility and security. While it applies primarily to federal government agencies and contractors, other organizations can also use it to improve their supply chain security. To get started:

- Incorporate C-SCRM into your procurement process: This includes embedding contractual language and risk assessments of services, suppliers and products throughout your lifecycle. Identify relevant C-SCRM controls based on this guidance and use them to conduct due diligence reviews and continuously monitor suppliers after procurement. This can include requirements of suppliers to notify of security vulnerabilities and incidents, the automated monitoring of supplier security profiles, and engaging with suppliers to discuss their security profile, including changes and enhancements. It should be expected that your second-line risk management staff will need to increase responsibility to oversee increased supplier risk management activities.

- Use existing information-sharing capabilities to incorporate supply chain risk considerations: Engage with vendors, partners, suppliers and information-sharing communities like ISACs, and use those experiences and best practices to mitigate upstream and downstream supply chain risks.

- Focus on awareness and training: SCRM may be new for many members of your team. Adopt enterprise-wide and role-based training programs to educate users on the potential impact of supply chain cybersecurity risks on the business and how to adopt best practices for risk mitigation.

- Adopt key practices and measures: NIST SP 800-161 Rev. 1 outlines several C-SCRM practices organizations should tailor and adopt at various levels, from executive support to operations. It also provides guidance for C-SCRM metrics development and measuring against overall risk tolerance, which helps benchmark organizational effectiveness in improving overall supply chain security. As firms expand and diversify their supply chain, the cost benefit of outsourcing responsibilities must be balanced with the cost of increased risk management oversight. This should be understood and accepted as part of the outsourcing discussion and is already recognized by purchasers like the federal government, the U.S. Department of Defense and large financial institutions.

The future of heightened software supply chain security expectations from government and regulated institutions is clear, and these expectations will likely flow down the vendor ecosystem. Improving your C-SCRM program today will help minimize the impact when your customers require stronger supply chain security.

Although reasonable efforts will be made to ensure the completeness and accuracy of the information contained in our blog posts, no liability can be accepted by IANS or our Faculty members for the results of any actions taken by individuals or firms in connection with such information, opinions, or advice.